Although anime conventions have re-opened their doors (with or without COVID-19 policies in place), we at Coherent Cats currently have no plans for future in-person panels. In lieu of convention appearances, here is a written addendum to Asexuality in Manga and More. Since we last discussed asexuality in manga, more and more relevant to the conversation have become available in English.

Please see Asexuality in Manga and More for an overview of Japanese terminology for asexual and aromantic identity. This post will primarily borrow the wording of the official English translations when discussing a specific series.

The rest of this post contains discussion of sexual content and anti-asexual and aromantic prejudice, as well as potential spoilers for all series mentioned.

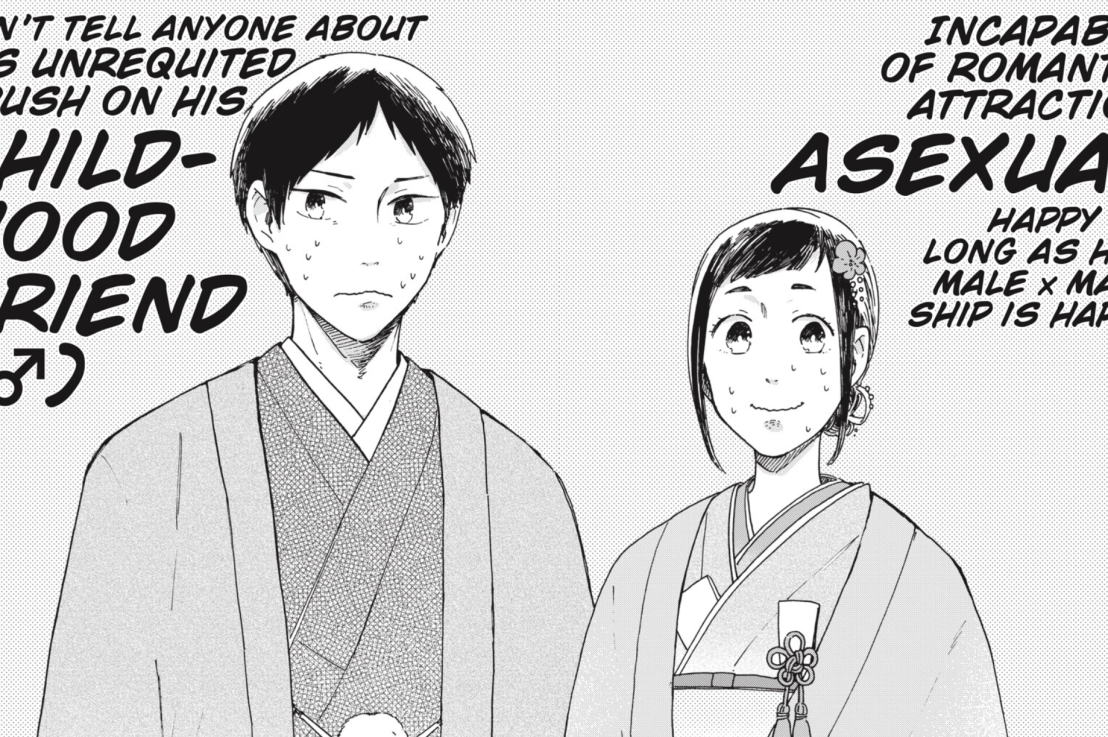

I Want to Be a Wall

The first volume of the josei series I Want to Be a Wall by Honami Shirono, which looks at a lavender marriage between an asexual woman and gay man, has recently been published in English. The translation describes Yuriko as asexual and “incapable of romantic attraction,” which in succinct English terms would be considered aromantic.

Yuriko has an appreciation for fictional romance as a fan of boys love, but does not desire romantic love or sex from other people. At one point, she muses on what draws her to the genre: “What I like about BL is that all the characters are men. There’s no girls, like the protagonists of shoujo manga or the heroines of shounen manga. […] It’s a place that has nothing to do with me. I can pretend like I don’t feel out of place.” With this, the manga pulls away from stereotypes that asexual people recoil from any sort of romance as well as that BL fans are straight women turned on by gay sex (not that there’s anything wrong with either). For Yuriko, BL provided an “escape” from the heteronormativity at her Japanese high school. She encounters more prejudice about being a virgin abroad in the United States, but also learns about asexuality as an orientation from a white Englishman there.

Yuriko and her husband Sousuke both have childhood flashbacks about alienation and frustration, with feelings they couldn’t identify until adulthood, drawing parallel lines between their situations that collided in marriage. Just as Sousuke had to watch his crush date girl after girl while keeping his love a secret, Yuriko had to watch her friend prioritize a boyfriend and be pressured by her to start dating too. Heteronormativity drove them apart from their peers, but ironically brought the two of them together.

They may be legally married, but they know they don’t romantically love each other. Instead, I Want to Be a Wall stands as one of the clearest depictions of a queerplatonic relationship in manga. They’re LGBTQ people committed to each other as husband and wife, but don’t have sex or even share a bedroom. They aim to support and learn about each other, but will never fall in love. The manga makes this clear with how elated Yuriko was to learn about asexuality, and how Sousuke has decided to always harbor a love for his childhood friend. It has the same fuzzy feeling as a love story, but will not inevitably lead to romance.

Though the English version from Yen Press provides many translation notes on Japanese culture and otaku fandom, it contains no definitions for asexuality or other information on Japanese LGBTQ culture outside the comic. The storyline already portrays them, but it seems like a missed opportunity for readers to learn more about asexuality in Japan.

I Wanna Be Your Girl

I Wanna Be Your Girl by Umi Takase, available exclusive on the digital app Mangamo, features an aromantic mentor figure to his young transgender, lesbian, and questioning students. Takase tells I Wanna Be Your Girl from the perspective of Hime, a cisgender girl with an unrequited love for her childhood friend Akira. When they start high school, Akira decides to wear the girl’s uniform and come out as a transgender girl to her classmates. Hime starts wearing Akira’s abandoned boy’s uniform in solidarity, though she doesn’t identify as trans and doubts the sincerity of her own actions.

In chapter 28, Akira asks for love advice from Sasaki-sensei after being repeatedly ignored by her crush in favor of Hime. Sasaki tells her, “you can’t stake the whole of your self-worth on someone else’s opinion of you,” and in the process comes out to her as someone who doesn’t fall in love with anyone. Chapter 29 delves into his past, where his classmates assume he has secret crushes and his family members beg him to get married and have children. In the present, he’s fulfilled by his bonds with his students. Society may act like aromantic people don’t exist, but he teaches Akira that you don’t need validation from others.

Takase uses an aromantic character like Sasaki to show how a person defines their own LGBTQ identity. Society perceives a person’s orientation by their current partner or history, which makes someone like Sasaki without any even harder to fit into a box. He identifies as aromantic even if others assume he’s a straight man and place heteronormative pressures onto him, just as Akira remains a girl even if her classmates misgender her. As a result, Akira lets go of the heteronormativity around being validated by attraction from a straight boy as well.

Mine-kun is Asexual

Irodori Comics has emerged as a new publisher of LGBTQ manga, specifically doujinshi available digitally. Their LGBTQ-themed doujinshi are published under the Irodori Sakura imprint, and one of their first releases was Mine-kun is Asexual.

Isaki Uta tells the story from the point of view of Tomoe Murai, a straight allosexual woman in college, who confesses to Mine, her bi and asexual friend. At first Mine hesitates to start dating because he’s sex-repulsed and worries a partner would expect to have sex. Murai likes him so much she decides to try dating without kissing or sex. Mine believes love and sexual desire aren’t the same thing, and is happy to find someone willing to give him a chance.

Their relationship goes well, though Murai admits she gets lonely. When one of her friends suggests that Mine is just secretly gay and manipulating her in order to appear straight, she defends him and shuts her down. Eventually they break up, but Murai makes it clear that Mine is in no way “lacking.”

Nameless Asterism

Nameless Asterism by Kina Kobayashi has love triangles and mistaken identity on par with Shakespeare. Middle schooler Tsukasa has a crush on her best friend Washio which she intends to take to her grave for the sake of their other close friendship with Kotooka, then finds out Washio actually likes Kotooka. At the same time, Kotooka keeps her love for Tsukasa as well as her knowledge of Washio’s feelings for herself a secret due to internalized lesbophobia. On top of all this, Tsukasa’s fraternal twin brother Subaru disguises himself as her and hangs out with his classmate Asakura to keep him away from the real Tsukasa.

Subaru goes to extreme cross-dressing measures to prevent Tsukasa from dating anyone because he emotionally clings to the idea of being one-and-the-same with Tsukasa, so the thought of her entering a romantic relationship with someone disgusts him. In Subaru’s mind, he can befriend Tsukasa’s BFFs Washio and Kotooka, but can’t date Tsukasa’s partner (regardless of gender). Even then, Subaru doesn’t understand the appeal of dating a stranger in general. When Asakura asks out Tsukasa after having never spoken to her before, Subaru finds it “creepy.” In English terms, he’d be considered romance repulsed.

When Subaru explains to Asakura that being confessed to would forcibly “label” him, Asakusa wonders aloud if he could be “aromantic” in the English translation. Subaru doesn’t recognize the term, and doesn’t understand putting a name to his feelings anyway. By distancing Subaru’s complex from labels, Kobayashi clarifies that he does not represent aromantic identity while at the same time acknowledging the existence and validity of aromantic people. Romance certainly repulses him, but that doesn’t necessarily make him identify as aromantic.

Asakura posits that Subaru could one day fall in love. Indeed, Kobayashi describes Subaru as “a boy who is afraid of change more than anyone–yet, ironically, ends up changing more than anyone.” By the final volume, he goes from seeing Asakura as his enemy to his friend. In a reflective inner monologue, he even says he didn’t know the true meanings of friendship and love “at the time.” Nameless Asterism ends with many unresolved conflicts and unrevealed secrets (including Subaru’s cross-dressing deception), so readers don’t know how and when Subaru’s understanding would change.

Perhaps if Nameless Asterism had run longer, the two boys would have eventually fallen in love. Unlike when Asakura asked Tsukasa out as a stranger, their friendship would serve as the basis for romance and dating. Instead of portraying aromantic identity as something to inevitably grow out of, it speaks more to fluidity and impermanence of perspectives and the self, similar to Bloom Into You by Nio Nakatani.

Sex Ed 120%

In Sex Ed 120%, storyboarder Kikiki Tataki and artist Hotomura combine sexual education facts with slice of life antics. A young physical education teacher named Tsuji resolves to educate her students about sex as well; starting with a lesbian in a relationship, a BL fangirl, and an aromantic asexual. Kashiwa describes herself as “not really interested in romantic love,” but takes intellectual interest in Tsuji’s lessons as a biology and zoology enthusiast. When she comes out about not understanding romance, her lesbian classmate Moriya notes the similarity between expectations to “find the right person” and for lesbians to “move onto” men.

Kashiwa’s presence makes it clear that everyone should have sex ed, even if they have no plans to date or have sex. Indeed, the second volume shows how anyone can be sexually harassed regardless of their gender presentation or sexual orientation when it happens to her. In general, Sex Ed 120% strives to be as inclusive as possible with how it touches on feminist issues and LGBT culture. In the third volume, Tsuji laments that “even if more people know about the the LBGT community, life is still difficult for asexual people in a society that considers romantic relationships the norm.”

The Vampire and His Pleasant Companions

The manga The Vampire and His Pleasant Companions by Marimo Ragawa adapts Narise Konohara’s novel series of the same name about a white vampire named Albert from Nebraska who accidentally ends up in Japan. Al finds himself in the care of a Japanese man named Akira, who agrees to provide Al human blood in exchange for help with his embalming business. Unfortunately Al has no fangs and little to no supernatural abilities, besides taking the form of a bat during the day and a human at night.

In human form, Al often sleeps in the same bed as Akira and even gives him goodnight kisses. Other characters assume they’re a gay couple, but so far they only have sexual and romantic tension. Al gradually falls in love with his roommate, while Akira makes his disinterest in dating anyone clear. When a gay coworker named Muroi asks out Akira, Akira turns him down even as “an experiment” the same way he’s turned down men and women before: “I don’t plan to pair up with anyone! […] I–I don’t feel any kind of desire for anyone! I’m frigid!”

At first Al doesn’t recognize the word frigid due to their language barrier, so Akira defines it as, “I don’t get turned on. I can’t get it up.” He describes his situation in physiological terms, but seems disconnected from sexual attraction on a social level as well. In another instance, he’s baffled when Muroi asks if he and Al “experiment” together when they’re alone. He doesn’t consider potential sexual situations the way others might, though seems painfully aware of his difference from other people.

After Akira explains, Al reassures him (in broken Japanese) that, “but… heart stand up. You love with your heart, it not like sex.” Al distinguishes arousal and sexual desire from love, encouraging him to date even if he won’t have sex. He knows Akira wouldn’t have sex with him even if they became a couple, but loves him anyway. Akira doesn’t repeat his intent to stay single, as if Al’s distinction between sex and romance makes a difference. He doesn’t identify as asexual, but Al still supports the idea of people who don’t experience sexual desire finding love. With the manga still publishing in English, it remains to be seen how exactly the relationship between them will develop.

How Do We Relationship?

The story of How Do We Relationship? by Tamifull begins when college classmates Saeko and Miwa drunkenly come out to each other as lesbians and subsequently try dating. Volume one does not directly involve asexuality, but touches on relevant issues. Miwa hesitates to have sex, though she has fantasized about it, which causes friction in their budding relationship. A straight friend named Rika assures her that not all couples have sex, which validates such relationships even if they aren’t represented.

Chapter 14 touches on expectations for sex and relationships again with another friend named Ucchi, who doesn’t see the appeal of being in a relationship compared to time spent by herself. When her friends insist being single is the same as loneliness, she gets insecure about the expectation for her to fall in love and mature into a woman. She explains that she would have to change herself to be accepted by society, and Miwa compares that pressure to her own as a lesbian and encourages Ucchi to live an authentic life.

I Think Our Son is Gay

Openly gay mangaka Okura tells I Think Our Son is Gay from the point of view of Tomoko, the mother of a closeted gay boy who wants to support her son without forcing him to come out. Her youngest son Yuri also supports his older brother Hiroki in subtle ways. When their father suggests that boys “normally” take interest in girls, Yuri asserts that he himself has “absolutely no interest in romance or girls.” In the first volume, Tomoko cannot tell if Yuri spoke from the heart or to just deflect from Hiroki’s hidden interest in boys.

In volume two, Yuri’s genuine disinterest in romance becomes more apparent. A flashback reveals that he once hurt a girl’s feelings by not going out with her, but he simply wanted to be friends. (Subaru has a similar backstory in Nameless Asterism.) In fact, he didn’t understand any of the romantic love between his classmates. He may not be as insecure about his orientation as his brother, but has still faced problems socially because of it. In the present, Yuri decides that his familial love for his brother satisfies him.

Even More Manga

There are plenty more “aro/ace-applicable characters” out there, even if they’re not at the forefront of their respective series. Other recent examples include but are not limited to Kira in My Androgynous Boyfriend, Izutsumi in Delicious in Dungeon, and Sasu in The Case Files of Jeweler Richard.

Of course, the manga listed here only scratch the surface of works available in Japan. There are probably many more manga incorporating and representing asexual and nonsexual identity that are unavailable or even unknown to us. For example, the boys love manga Hatsukoi Catharsis (“First Love Catharsis”) by Nuko Hatakawa follows the relationship between a self-identified nonsexual man and an allosexual man.

In the English manga market, we have more on the way. Kodansha announced the license of Is Love the Answer?, another manga by Uta Isaki (creator of Mine-kun is Asexual). The self-contained volume follows an aromantic asexual woman navigating amatonormative society. More manga by the openly asexual mangaka Yuhki Kamatani are available than ever, including the ongoing Hiraeth: The End of the Journey and the upcoming Shonen Note: Boy Soprano.

Observations

When you look at all these manga (including those in Asexuality in Manga and More), some patterns start to emerge. For one, some of these manga began digitally on Pixiv (Hatsukoi Catharsis, I Want to Be a Wall) or were self-published (Mine-kun is Asexual). These alternative avenues from printed magazines may allow more freedom to explore asexual and nonsexual identity, just like zines and webcomics among English-speakers.

Asexual and nonsexual characters also tend to appear in manga delving into sexuality and/or romance: Scum’s Wish, Devils’ Line, Bloom Into You, etc. They question what constitutes romance, how sex plays into it, and what society expects of people. These issues apply to anyone regardless of orientation, but it’s interesting to see asexual and nonsexual characters included specifically.

Similarly, asexual and nonsexual characters tend to be found in manga with other LGBTQ characters, including stories about LGBTQ social issues. I can’t account for every manga in existence, but every title listed here with a designated asexual/nonsexual character also has at least one lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender character. Sometimes they are one and the same: Kanzaki in Devils’ Line, Mine in Mine-kun is Asexual, Someone-san in Our Dreams at Dusk. Other times, they may be a side character in a manga with another main LGBTQ character: Kashiwa in Sex Ed 120%, Sasaki in I Wanna Be Your Girl, etc.

Asexual and aromantic share spaces with LGBTQ more often than not, which includes the manga genres of boys love and yuri. Both genres have increasingly incorporated LGBTQ vocabulary, such as lesbian in Still Sick and gay in Go For It Nakamura. As realistic gay and lesbian portrayals continue to grow in yuri and BL (not that there’s anything wrong with the more divorced from real life), so apparently will other LGBTQ identities like asexual and nonsexual. Manga like Sex Ed 120% and I Think Our Son is Gay look at BL and yuri from an LGBTQ lens, and also advocate for respecting asexual people in their exploration of social issues. Representation should not be seen as competition between identities, but rather how intertwined they can be in manga.

If you enjoyed this article, you can support me with a tip by buying me a coffee. Thank you!

Great article – thanks for putting the hard work in to round up all these series!

LikeLike

A truly informative, detailed and wonderful post! Thank you very much for writing this!

LikeLike

Thank you for writing an update to your original post! Both that post and this one helped me a lot in finding ace secondary characters. Although I will say, it does make me sad to see a list of ace manga without the masterpiece that is Yuri to Koe to Kaze Matoi on it (;_;) (I assume because it’s not available in English?) But especially with Isaki Uta’s much more robust follow-up getting translated this Fall, it’s definitely an exciting time for ace manga in translation!

LikeLike