In honor of the publication of the final volume in Japan and the English license from Seven Seas Entertainment, it’s finally time for an in-depth look at Yuhki Kamatani‘s Shimanami Tasogare: Our Dreams at Dusk. The manga follows Tasuku, a teenage boy coming to terms with being gay after a failed suicide attempt. In his hometown of Onomichi, he discovers an LGBTQ-friendly lounge through its aloof owner known only as “Dareka-san” (Someone-san). Over the course of a year, Tasuku comes to know the community of the drop-in center and their housing renovation organization Cat Clutter.

In Kamatani’s Onomichi, the characters’ surroundings often mirror their states of mind: freedom, confusion, joy, frustration, fear, redemption, and more. As the characters express more of themselves, and to acquaintances, they don’t necessarily come to a better understanding of themself or others. Still, their journeys and relationships to identity reveal many facets of LGBTQ life. Together, they build and maintain community in the face of oppression.

This post contains spoilers for all of Shimanami Tasogare. Do not read it if you wish to remain unspoiled for the English edition coming in May of 2019.

Tasuku: Acceptance

We’re introduced to Tasuku, our protagonist, aware he’s attracted to fellow boys but afraid to admit he’s gay to other people. When his classmates suggest he could be, he denies it by calling gay people sick. Disgusted with himself and terrified of returning to rumors at school, he attempts to commit suicide and Someone-san interrupts. From then on, his life changes for the better and he comes to accept himself.

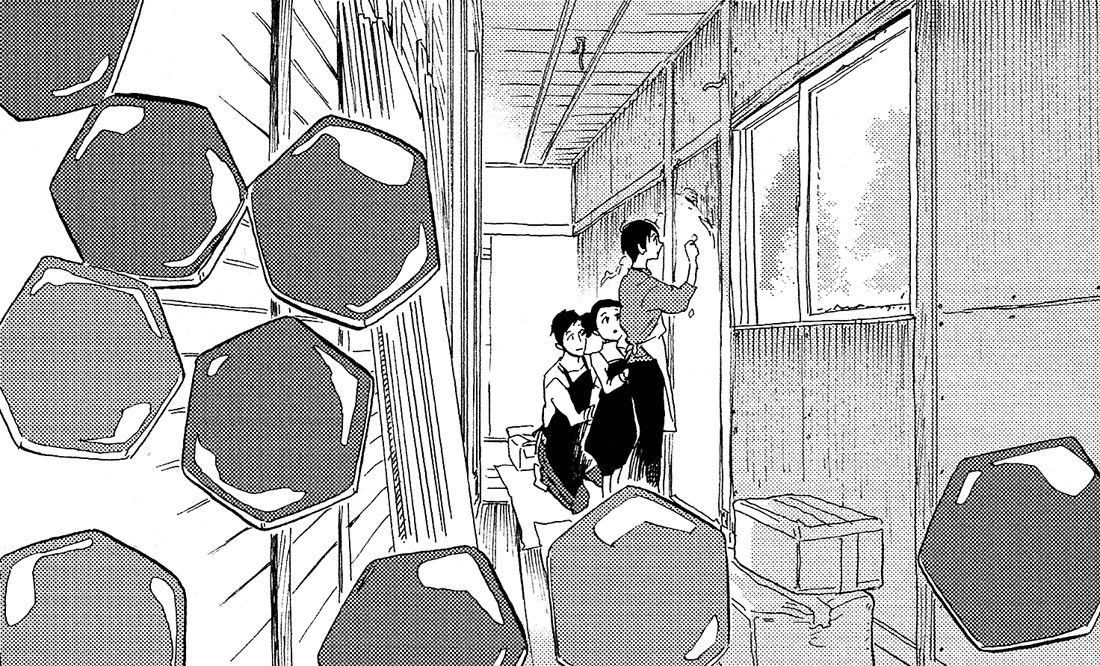

When Tasuku returns to school the next day, his surroundings warp as classmates call him slurs and speculate on his sexuality. The room bends from rigid to swirled, even when other students call them out for homophobia. No matter who’s discussing his sexuality or how, he loses ground in the room without a say in how others see him. He’s not in control, not part of the conversation, and thus drifts from the classroom to a background of pure black. When he shouts at them to stop, the room comes back into focus only for Tasuku to dash into a looming hallway.

With nowhere else to go, Tasuku follows up on Someone-san’s offer to visit a drop-in center. Unlike the classroom, the drop-in center is to scale and in focus in its establishing panel. Someone-san welcomes Tasuku into their private quarters within the building, where he confides to them that he might be gay. The drop-in center has provided him a space to be honest about his feelings and identity, but he still he imagines the school lockers towering over him as he worries about rumors spreading. The guests offer him a seat and music to decompress after crying out his anxieties. The drop-in center doesn’t always comply to physical reality, but rather than change in shape like the classroom, the moods of the characters or music played manifest within the walls. The sounds of “Winter Daydreams” billow from the record player and intermingle with the guests, entering their mouths like a breath of fresh air. The drop-in center exists as a place where marginalized people’s feelings transcend physicality, instead of being repressed elsewhere.

Daichi, the designer of the drop-in center, offers Tasuku to join her housing renovation organization Cat Clutter. He’s taken aback by the idea someone could want him around, to be part of their community. Daichi comes out to him as a lesbian in a relationship, but even in the safety of the drop-in center among fellow LGBTQ folk he denies being gay when asked. She also offers an empty building, dubbed Triangle Manor, for him to take creative control of. When they go to collect broken boards from the manor, Tasuku watches Daichi caress her wife and imagines doing the same to his classmate Tsubaki. His chest bursts into images of them together, like the fragments of demolished boards. When Daichi reaches out to the frozen Tasuku, his body splinters entirely. Like the house, his identity must be broken down before it can take shape.

Tasuku later volunteers to demolish a wall of Triangle Manor, but trembles with the crowbar. Daichi gives him a nail puller to start small and make the boards easier to remove. When he removes a nail, he peers through the hole it leaves and sees Tsubaki and Someone-san–two people he wants to become closer to. He can’t make the leap of coming out like Daichi yet, but can work up to it with them in sight. He confesses to Daichi he’s fallen in love with a boy. It’s not exactly identifying as gay, but a step to being open with her and accepting himself. Afterword, school is rendered realistically as Tasuku’s anxiety there has somewhat subsided.

Daichi: Honesty

Just like Daichi offers the house to the closeted Tasuku, Someone-san gave her a building before her family knew about her sexual orientation. When her father says he pities the parents of same-gender couples, the objects and surroundings of the dining room disappear, leaving only the gap between her and her parents. There is not only a physical separation, but an emotional one. She wants to hold out for the future in her personal life, just like she holds out on deciding how exactly to demolish the building. In her moment of hesitation, Someone-san hacks away at a wall to demonstrate how something planned can be started any moment. As Daichi finishes tearing down the wall, her crowbar breathtakingly pulls back on a board overlayed with coming out to her parents to reveal the current scene. On the next page, she stands with her partner Saki between the beams in the sunlight. By being honest about her identity and dreams, her world opens up to a bright future.

Daichi finds a new life in Onomichi after severing ties in Hiroshima, including building the drop-in center where people are free to be who they are. She wants to fill it with people and their spoken truths, unlike that dinner when she couldn’t reply to her father, and she succeeds. From then on, she always speaks her mind and calls out straight people for homophobia. Such confidence makes her an example of LGBTQ adulthood to Tasuku, as well as a mentor. Throughout the story, Daichi fosters her community by guiding the other characters in their endeavors and checking in for clarity of how they feel about a situation.

Saki: Hesitation

However, her partner Saki isn’t open with her parents about being a lesbian. She’s in the position Daichi was before meeting Someone-san: waiting for the right time. However, Daichi supports her as they plan for the future. For now, she has the communities of the drop-in center as well as her family’s bar. She exists in the same space as her family at the bar, but they don’t entirely know her like at the drop-in center. When Tsubaki’s father outs Saki to her own father, she worries she’ll lose that connection. She’s also been robbed of the opportunity to explain her identity on her own teams. Thankfully, her father apologizes for the homophobic refusal that his daughter could be gay and her parents accept her.

Daichi takes Tasuku under her wing, giving him a gay role model and safe space to exist. He learns about the different options for coming out from her and Saki. In return, he proposes using Triangle Manor for their wedding and reception. The space that represents his freedom of self also serves to foster his newfound community. At the wedding, Saki’s biological family and LGBTQ community can finally come together under one roof.

Misora: Patience

Through the drop-in center Tasuku also meets the younger Misora, and forms a precarious bond with them. The drop-in center offers Misora a space where they can dress how they want and be complimented by others, not unlike the bowl of goldfish they take care of there, with a closet of items donated by other guests. Tasuku assumes Misora likes boys based on their cross-dressing, in a display of how gay men are not immune to insensitivity. Misora says they simply wear the clothes they want to.

Outside the drop-in center, they present as a boy, such as when they visit Tasuku’s bedroom to discuss a wet dream. It’s a cramped space within the family home, but it doesn’t necessarily bring them closer: when Misora says no one understands them and leaves Tasuku speechless, the wide panel of them across from each other makes a small room appear cavernous. Before Misora can run away and widen the gap between them, Tasuku suggests introspection to better understand themself.

Tasuku has trouble understanding Misora, because any label he suggests they respond with uncertainty. Misora complains that Tasuku’s explanation for realizing he’s gay, of when a good-looking classmate simply made him aroused the first time, isn’t easy to understand either. As they try to comprehend each other’s identity they butt heads, but overall get along. Misora admires that Someone-san grew into adulthood without being anything specific, but Tasuku wants to fill that mentor position instead. Tasuku pushes for them to accept an identity, whether transgender or cross-dresser or otherwise, like he did.

Misora finally steps out of thedrop-in center presenting how they want, taking the support of their community imbued in a goldfish print kimono into society. The drop-in center provided freedom, but was as confined as the fishbowl. At the festival, Misora says they want to dress like a girl in public more. They catch a pair of goldfish and carry them in a bag, a more mobile way to live. Unfortunately, a stranger gropes them and Tasuku’s victim-blaming throws all their progress out the window. Misora’s snarls with rage, shouting slurs at Tasuku. In the scuffle, the goldfish nearly fall to their deaths (to be rescued by Tsubaki). As soon as Misora finds a more open way to exist, like the goldfish, it’s taken away.

The incident hurts so much that Misora can’t even confide in Someone-san, and they stop visiting the drop-in center. Tasuku’s mistake of blaming the assault on Misora’s appearance, the thing bringing them happiness, causes them to abandon their support system and only avenue to exploring presentation and identity. After the fight, Tasuku goes to reflect in Triangle Manor and imagines it collapsing onto him. He decides the building doesn’t need a specific idea so soon, paralleling how Misora doesn’t need to have a specific identity at the moment. Indeed, the end of the manga doesn’t label Misora, leaving it to the future. Their identity is open to interpretation, but claiming one definitively may miss the point.

Mai: Opportunity

Cat Clutter invites local children to make tiles to decorate an upcoming art gallery. A young girl named Mai creates a collage in the shape of a boat, but her mother wants her to make something cuter, apparently because it would be more “appropriate” for her gender. The moment introduces Koyama, her mother, as someone who forces her ideas onto others. Later, Tsubaki offers Mai the leftover tiles to decorate the walls of Triangle Manor, which gives her an artistic option outside her mother’s influence. Triangle Manor can be a place for others to express themselves, not just Tasuku.

However, Koyama oversteps again and forces suggestions for Triangle Manor’s renovation onto Tasuku, until Cat Clutter member Utsumi says it’s not her decision to make. While she pushes Utsumi to attend their volleyball team reunion, Mai picks up a box of tiles and drops it. Unfortunately, in creating a distraction to rescue Utsumi from pushy her mother, she breaks her means of expressive freedom. At the moment, severing Koyama’s connection to Utsumi may also revoke Mai’s connection to Cat Clutter. Thankfully, Utsumi and Koyama do attend the reunion, while Mai bonds with her babysitters at the drop-in center. She also hangs around the goldfish bowl, echoing Misora’s means of freedom. She finally has time and space to exist away from her mother, allowing her to meet LGBTQ people as they are.

Utsumi: Tolerance

Utsumi says he doesn’t get worked up about whether others accept him as a transgender man or not, unlike Daichi who wants recognition of her identity. For him the drop-in center isn’t so much a place to exist openly, but a place to exist without expectations and prodding. Different LGBTQ people have different needs and relationships to their identity, and a single space can provide for many. He also has his group of local cyclists, who presumably don’t know he’s trans, for community.

Even though Koyama deadnames him and asks invasive questions, Utsumi reacts cordially to her. Her chipper “good intentions” are formidable, just like the ship about to cross a smaller boat on the Onomichi Channel in the background when she reunites with Utsumi. She pledges to support her old friend, and her benevolent flavor of transphobia makes it difficult to call her out. If she’s tolerant of his identity, he must be tolerant of her ignorance too. Utsumi works with plaster, as he does in tandem with their conversation, so he knows how to smooth over something rough. It’s only until she insults the other members of the drop-in center, by saying being transgender is a medical disorder more justifiable than being gay, that he openly resents her. Tasuku and Utsumi have a heart-to-heart, like he’s had with Misora, on the Shimanami Kaido. The wide open space of the bridge (visually similar to the beams of Daichi’s eventual drop-in center) allows Utsumi to be honest and shout his frustration, unlike the confines of Triangle Manor.

As much as Koyama claims to understand being trans, she sees it as a disease and uses that as a means to disregard gay people. She even wants Utsumi to speak at Mai’s school about it. However, Utsumi has no obligation to educate or serve her after she’s proven herself to insensitive. In the words of Karl Popper, “if we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.” Utsumi’s breaking point makes Koyama apparently realize the error of her ways, and she leaves Cat Clutter and loses that community.

He doesn’t owe activism to anyone, especially not an ignorant “ally.” Kamatani described their own position as similar to Utsumi’s in an interview for Anime News Network: “I admire those who raise their voices, but can only quietly support and cheer them on from the sidelines. What I can do is draw comics that provide an opportunity for people to think about these issues.” They may not be activists, but can protect their communities and retain personal boundaries in other ways.

Tsubaki: Conciliation

Tsubaki works with Cat Clutter and hangs out in the drop-in center, despite his apparent distaste for gay people. Around Tasuku, he often initiates intimacy between them, such as pulling him close and smirking, leaving Tasuku confused as to Tsubaki’s motivations. When Tsubaki demands Someone-san about their orientation and gender assigned at birth, they flip the script and ask if he’s a girl or gay. When apparitions of Someone-san appear at school and Tsubaki starts to question himself, he stops visiting Cat Clutter.

Whenever Tasuku becomes frustrated with Tsubaki’s mixed messages or outright homophobia, the school setting fades to black and Tsubaki hovers in a UFO above him. They may be together physically, but they’ll never make a genuine connection as long as Tsubaki doesn’t exist on the same plane emotionally. Tasuku reaches a breaking point and metaphorically climbs into the UFO when Tsubaki says the LGBTQ members of Cat Clutter disgust him. He sees the open community not as something to celebrate, but an invitation to be attacked (by him and more). Tasuku defends his friends, then comes out as gay as well as confesses to being in love with him. Then, the UFO reverts to their classroom and finally they can see eye-to-eye on solid ground.

From then on, Tsubaki resolves to no longer hurt others and even stands up to his father’s homophobia. Still, he cannot figure out if he’s attracted to men. Having learned from the fallout with Misora, Tasuku tells him there’s nothing wrong with being unsure. After chapters upon chapters of Tsubaki’s malicious advances, they have a genuine hug wherein he lets out his true feelings. The hug lasts for six whole pages, with lovingly rendered panels of Onomichi interspaced between as a reminder they’re hugging in public. Even in a city with thousands of people, two can make contact as intimate as if they’re alone.

The day of Daichi and Saki’s wedding, Tasuku and Tsubaki find Triangle Manor defaced with slurs. Tasuku freezes, seeing an extension of himself attacked by his worst fears, but Tsubaki gets the idea to thin the paint. He erases the hurtful words he only recently stopped using, to ease Tasuku’s anxiety and save their community event. By rejoining them, he’s symbolically easing the pain he caused. Societal heterosexism is so powerful it can warp the thoughts of people into internalized homophobia, which manifested differently in Tasuku and Tsubaki. Tasuku said hurtful things to fit in knowing they applied to himself, while Tsubaki antagonized other people out of confusion rather than look inward. Now, Tsubaki has to apologize. The communal presence of those determined to make up for past bigotry may even be necessary, since the graffiti may have gone unsolved without him there. Tsubaki has owned up to his past, and found a new community where he can navigate his identity.

Ilya: Connection

Ilya, also known as Tchaiko-san after the famous (and agreed to be gay) composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, has struggles unique to being the oldest member of the drop-in center. His partner of 30 years is terminally ill, and Ilya wants to keep their relationship a secret from Seichirou’s family. Their lives, which began before societal changes the others have, are coming to an end. Seichirou can’t be part of the drop-in center community as he lives in a local hospital, but still connects to Ilya via instant messaging. Only the hospital room provides physical proximity.

However, Seichirou’s son from his previous marriage and Ilya can’t both exist in the hospital room. Unlike Saki’s family’s knowledge of Daichi as her “roommate,” his son Akira has no idea Ilya exists. They pass by each other in the hallways of the hospital, Akira unaware. Ideally they could all come together as a family, but Ilya has resigned himself to not disrupting the only recently reconnected father and son. Unfortunately without Akira’s consent, Ilya won’t be able to see his partner as he dies. In the end Someone-san, usually uninterested in the relationships of others but now overcome with emotion, convinces him to break through hesitation. After years of friendship, that may have been the most vulnerable they ever saw each other.

Seichirou’s two most precious people finally meet under one roof when he enters critical condition, and Akira uses his father’s phone to encourage Ilya to join them. The tool that kept them together across physical reality also connects the three of them. Ilya’s touch reinvigorates Seichirou, who leaps into the air with a regrown head full of hair. Their love is not bound by physical restraints, as it makes them float above the hospital bed. After saying goodbye, a lovely two-page spread shows a single ship sailing down the Onomichi Channel, away from a panel of Seichirou’s lifeless body obscured by Akira and Ilya. His soul has departed Onomichi, but they’ll always hold onto him.

Someone-san: Inscrutability

Someone-san brings citizens of Onomichi into Daichi’s drop-in center, where they have their own private room. It creates a physical as well as emotional separation between them and the guests, despite being the owner. Someone-san generously offered the drop-in center to Daichi to build her identity, but their most vital gift is simply providing a sounding board. They stand by while others confess their innermost thoughts, which as LGBTQ folks they usually have to keep bottled up. Someone-san provides the privacy to let them out with no judgement, no repercussion, no advice. Sometimes you need a one-sided conversation, which all members of the drop-in center have presumably had with them. (When Ilya voices his fears about facing Akira and Seichirou, Someone-san reacts emotionally for the first time, because some times call for intervention too.)

Throughout the story, the art indulges in surrealism to accentuate Someone-san’s detachment from the other characters. They materialize apparently out of nowhere, jump from ledges and float on rather than fall to their demise, and fleet in and out of vision. At first it seems Someone-san will remain an intangible, metaphorical presence in Tasuku’s new dreamlike life, but they are in fact a real person. When Daichi says she’s shocked Someone-san would invest in others enough to make them all lattes, Tsubaki reprimands her. He may have been visited by taunting apparitions of Someone-san, but he stands up for them and says they’re a human being with an inner life like anyone else.

Maybe Someone-san truly can fly and disappear, or maybe it’s all an exaggeration from Tasuku’s perspective. It ultimately doesn’t matter if the imagery is literal or not, because the sentiment someone could be so unknown to you is true to life. That’s the power of Kamatani’s melodrama. Tasuku has to accept that he’ll never comprehend some people, but that’s different from knowing and respecting them. Although it may seem to him that Someone-san’s “lack” of sexual or romantic desire makes them aloof, that isn’t the case. Their surreal eccentricities aren’t a metaphor for their asexuality, either. As soon as Tasuku manages to cradle a darting, symbolic Someone-san in his hands, the real one before him lifts off the ground. They can’t be pinned down so easily: Someone-san explains being asexual as just one aspect of who they are, not that being asexual determines who they are, just like being gay for Tasuku. When they were younger, they felt ashore while others sailed ships of “man” or “wife” or “rival,” and embraced a life of anonymity as well as the identity of asexual.

Someone-san embodies the central idea of Shimanami Tasogare: one does not need to be understood to be respected. For Someone-san, the fact they cannot be easily understood by others is vital to their own conception of self. Coming from a character with a more “obscure” LGBTQ identity makes it all the more poignant, but every character longs for that respect (even if they don’t realize at first). Tasuku wants it from Tsubaki, Daichi and Saki from their parents, Misora from Tasuku, Utsumi from Koyama, Tsubaki from his father, and Ilya from Akira. Someone-san finally receives it from Tasuku when he pushes through the nebulous possibilities of their identity–people, animals, even objects–to simply take their hand.

If we can’t provide a physical drop-in center to others, we can at least lend a hand of respect. Considering the journeys we may take to reach an identity, especially one LGBTQ, we owe it to each other to accept them at their word. Maybe we’ll come to understand each other better over time, or maybe not, but being together nurtures the support, solidarity, and progress we need.

You can support Kamatani, an asexual and x-gender creator, by pre-ordering Shimanami Tasogare in English. If you enjoyed this article, you can support me with a tip by buying me a coffee. Thank you!

Really great write up! I especially liked your careful attention to how construction, demolition, and architecture is used as symbolism throughout the story. Some of it I had previously noticed, but other instances were new to me. And I appreciate your point about Misora–I see a lot of people labeling Misora as a trans girl (and perhaps it’s true) but the story leaves it open-ended and I think that’s important to acknowledge. I’m looking forward to reading the upcoming English release a lot!

LikeLike

I finished reading this manga yesterday and stumbled upon this article while looking for others’ thoughts on it. All I have to say is this is truly an excellent analysis of the characters and symbolism in the story. Thank you for writing it!

LikeLike