This post has been long overdue, as the convention panel it’s based on was first held at Kumoricon in October of 2018. The Asexuality in Manga and More panel is a collaboration between myself and Modulus, my aroace friend.

Our Dreams at Dusk: Shimanami Tasogare, the latest manga by openly asexual mangaka Yuhki Kamatani, is finally available in English! This is only one of many increases in visibility of Japanese asexual people and representations of asexual identity in Japanese media. Let’s take a took at the emergence of asexual and nonsexual characters in anime and manga, as well explorations of sexuality and relationships adjacent to asexuality in other titles.

The rest of this post contains discussion of sexual assault, anti-asexual and aromantic prejudice, and potential spoilers for all series mentioned.

Terms and Definitions

Before we get into the media, we need to explain some terminology. Even if you’re familiar with asexuality in English, there are some differences in Japanese. This is about Japanese media, so will be approached from a Japanese perspective as much as possible. We may share experiences with Japanese asexual folks, but for now just put what you know in English out of your mind. If you’re unfamiliar with asexuality in English, it’s hopefully still easy to follow.

Asexual (アセクシャル, Aセクシャル, 無性愛)

In English, asexuality is a sexual orientation defined by not experiencing sexual attraction. In Japanese, “asexual” means experiencing no sexual nor romantic desire, making it equivalent to “aromantic asexual” in English. It can be shortened to “aseku,” like English speakers shorten it to “ace.” There are two ways to say asexual: the loanword “asekusharu” (アセクシャル), or the Japanese word “museiai” (無性愛) literally meaning “no sex love,” or “no sexual love.” The noun for an asexual person is “museiaisha” (無性愛者). In Japan all formal words for sexual orientation use “seiai,” meaning “sexual love.” From a Whorfian linguistic point of view (in which the language a person speaks affects their worldview), you could argue that sex and romance are conflated in Japanese society based on this etymology. That may be why asexual has an inherent aromantic element that it doesn’t in English.

Nonsexual (ノンセクシャル, 非性愛)

The word “nonsexual” (ノンセクシャル) as a sexual orientation is wasei-eigo, meaning it’s a word used in Japan based on English but isn’t used in English. In Japanese, nonsexual means experiencing romantic desire and no sexual desire. It can be shortened to “nonseku.” The Japanese formal word for nonsexuality is “hiseiai” (非性愛) meaning “non sex love” or “non sexual love.” The noun for a nonsexual person is “hiseiaisha” (非性愛者). Basically, nonsexual people can pursue and have romantic relationships with others and not be sexually attracted to them. They may or may not have sex, but don’t experience a desire toward other people. Nonsexual people can describe their romantic and sexual desires in tandem with nonsexual or hiseiai. For example, “gei no nonseku” (ゲイのノンセク) or “gei de nonseku” (ゲイでノンセク) could describe someone who’s gay and nonsexual.

Aromantic (アロマンティク)

The loanword “aromantic” is not used in Japan as much as asexual or nonsexual, from what we could find. There is not a formal Japanese word for it. Some use it in the context of the English loanword “aromantic asexual,” some in an emerging Japanese usage for no romantic feelings. With the meaning of Japanese “asexual,” it is unclear what place “aromantic” has in Japanese at the moment. If “asexual” always means a lack of sexual and romantic desire, perhaps “aromantic” could be used for people who have sexual desire and no romantic desire.

To summarize, in Japanese “asexual” means having no romantic nor sexual desire. In English, we’d call that aromantic asexual. In Japanese “nonsexual” means having romantic desire and no sexual desire. In English, we could call that alloromantic asexual. “Asexual” can also be used as an umbrella term for asexual, nonsexual, and their spectrums (as it will often be used in this post). However, that’s not to say split attraction and English terminology in general aren’t used in Japan. There is crossover through cultural exchange and Japanese people will use the terms most useful to themselves or the situation.

Related Words

We have more loanwords from English to cover. They seem to be in less use than the others we’ve covered, but they’re important nonetheless. These concepts aren’t exclusive to English-speaking Westerners.

Asexual, nonsexual, aromantic, etc. fall under the Japanese meaning of “sexual minority,” which overlaps with and may be used interchangeably with terms such as LGBT or queer. It can be said as “seiteki shousuusha” (性的少数者) or the loanword “sekusharu mainoritii” (セクシャル・マイノリティ), often shortened to “sekumai” (セクマイ). It covers people in a minority related to sexuality, sex, or gender as an umbrella term.

A queerplatonic relationship (クィアプラトニック関係, クィアプラトニックな関係) is an intimate and committed platonic relationship between people. They’re not exclusive to asexual or aromantic people; anyone may have a queerplatonic relationship and partner. In Japanese, “queerplatonic” may be said with “na” (な) attached to the end before “kankei” (relationship) because loanwords are usually na-adjectives.

As you know by now, Japanese distinguishes romantic and sexual desire differently from English. However, the loanword allosexual (アルロセクシャル) appears in some Japanese sexuality glossaries. In English, allosexual means not asexual. In Japanese, it means not asexual nor nonsexual. In either language, it describes people without calling them simply “sexual.”

Grey-asexual (グレイアセクシャル) means sexuality in gray area between asexual and allosexual. Presumably in Japanese this could mean gray area between asexual, nonsexual, aromantic, and more. Demisexual (デミセクシャル) means sexual desire when only emotional bond to another person is formed. Grey-A and demi can be used in tandem with identities like gay, bi, and more as well.

“Seikeno” (性嫌悪), meaning sexual aversion, is the Japanese equivalent to the English term “sex repulsed.” Being sex averse means being repulsed by engaging in sexual intercourse, and/or sexual intercourse in general. Asexual people use these words in Japanese and English to describe their relationships to sex, but it’s not an experience exclusive to them. Anyone can be sex repulsed.

Not Asexuality

The Japanese word for asexual reproduction is “musei seishoku” (無性生殖), which contains “musei” meaning “no sex” the same as in “museiai.” Just like in English, asexuality sounds similar to asexual reproduction, but they are different things. Asexual reproduction means reproduction from and by a single organism. That’s all.

A more complicated distinction comes with “herbivore men” (草食系男子), a buzzword from the last decade for Japanese men who are not in pursuit of romantic relationships, marriage, manliness, and/or sexual gratification depending on the definition. There’s a lot to unpack here about how apparently sexuality defines manliness, how people feel the need to comment on when men act outside social norms… but that’s outside the scope of this article.

Personally we find the sensationalism around “herbivore men” more noteworthy than a supposed new trend in how men behave. The vagueness of the term allows people to apply it to anyone they see fit to comment on men in modern society. There’s also the issue of Western journalism sensationalizing the issue because it fits the stereotype of desexualized East Asian men. If you’ve been around online English asexual communities long enough, you may have seen these articles shared with the claim that the prominence of herbivore men means Japan accepts asexuality. However, society doesn’t accept herbivores because they don’t fulfill gender roles or heteronormativity, so it doesn’t make asexuality any less stigmatized. Men deemed or self-described as herbivores are not necessarily asexual. Asexuality is a personal identity of sexual orientation you have to decide for yourself, while men are labeled herbivores by other people for a number of reasons.

Another issue regarding asexuality is in the medical system and psychological community. This topic is especially outside our scope (though we do go more in-depth when presenting this panel at conventions), but to be brief for this pop culture-centric blog: diagnoses are not the same as sexual orientations. Sexual aversion disorder (性嫌悪障害) and hypoactive sexual desire disorder (性的欲求障害) from the discontinued DSM-IV-TR are not equal to asexuality, and neither are male hypoactive sexual desire disorder and female sexual interest/arousal disorder from the currently used DSM-V.

Sources/Further Reading

- What is Asexuality? (English)

- Asexuality Archive (English)

- What Is The Difference Between Aromantic And Asexual? (English)

- Aromanticism and the aromantic spectrum (English)

- A History of Words Used to Describe People That are Not Asexual (English)

- Asexual.jp information page (Japanese)

- Asexuality resources from Stonewall Japan (English/Japanese)

- Asexuality in Japan: a conversation with harris-hijiri (English)

- No Romantic Feelings: Asexuality in Japan master’s thesis (English)

- Masterpost of Queer as Cat posts on asexuality in Japan (English)

- QAC 73 – 【Asexuality In JAPAN】An Interview ♠ (English/Japanese)

- All Queer as Cat posts tagged #aces in japan (English)

- All posts about asexuality by Chii (Japanese)

- Japanese translations of Tumblr posts about asexuality and aromanticism (Japanese)

- Sexuality A to Z (Japanese)

Asexual Mangaka Spotlight

Yuhki Kamatani

In English-speaking fandom there’s a lot of talk of asexual, aromantic, and nonbinary headcanons; but not so much about creators. Not only is mangaka Yuhki Kamatani asexual, they’re also openly x-gender (a Japanese nonbinary gender identity). People owe it to themselves to check out the work of someone in those demographics.

Kamatani has been professionally creating manga since 2000 at 17 years old. Their stories often involve adolescence, identity, and accepting change. Only Nabari no Ou and Our Dreams at Dusk: Shimanami Tasogare have been licensed in English. Kamatani came out as asexual and x-gender on Twitter in 2012 (though their Twitter account has since been deleted). They have also described themself as “sekumai,” a sexual minority. In an interview for Anime News Network, they said their opinion on LGBTQ issues can be difficult to put into words. Instead, they create manga with LGBTQ issues and representation to bring attention to them.

Sources/Further Reading

- Intro to the Works of Yuhki Kamatani (by yours truly, English)

- Art as Discovery, Art as Hope: Yuhki Kamatani, x-gender and asexual mangaka (by yours truly for Anime Feminist, English)

- Speak Out! Japan’s LGBTQ+ Community Responds to Politician Sugita’s Discriminatory Statements (English)

- Interview for Shounen Note (English, originally Spanish)

- Interview with Buzzfeed Japan (Japanese)

Nabari no Ou

Nabari no Ou, a shounen manga serialized from 2004 to 2010, has been out of print in English for some time (as of this article’s publication). As one of Kamatani’s only manga available in English, it’s worth a look from an aromantic and asexual perspective. Kamatani has described Nabari no Ou as a turning point in their career where their work “became truly mine,” as they had a moment of self-discovery shortly into serialization. That may or may not involve their identity of asexual, but the manga can nonetheless be seen as a reflection of Kamatani. An anime adaptation also exists, but it has a different ending since the manga hadn’t finished at the time of production.

The story follows Miharu, a young boy who discovers he harbors a spirit known as the Shinrabanshou with the power to rewrite the universe. However, that doesn’t mean he knows how to use it or even wants to. A secret society of modern day ninjas seek him out for his power, but he doesn’t want anything to do with them. He’s content to live a life of indifference alone, but learns to open up as well as make friends and allies over the course of the series. There are too many relationships to cover in-depth in this post, sadly.

The world of Nabari no Ou comes across as rather chaste. Romantic couples exist and some have biological children, but no sexuality on display… with one notable exception. You know how shounen manga usually have that “lovable” perverted guy character? This story has one of those, but he’s not intended to be likable. Not in the way girl characters groan at Mineta in My Hero Academia for leering at them and he keeps going, but that the character is unforgivable and irredeemable for much more important reasons. Without giving away plot details, it’s satisfying compared to other series where you’re supposed to respect some old guy who sexually harasses young girls.

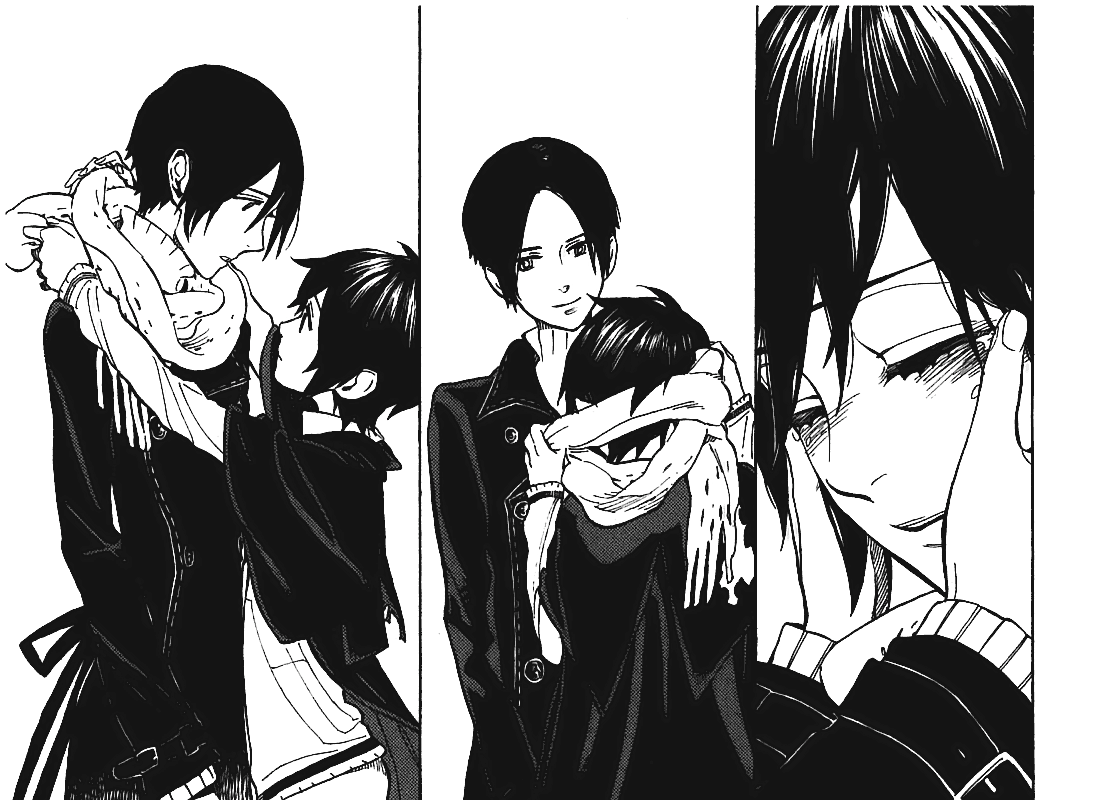

The more important point regarding (a)sexuality is Miharu and Yoite’s bond at the heart of the story. Their relationship begins when Yoite requests for Miharu’s power to make it so they never existed before their body degenerates from use of a forbidden ninja technique. They’re both disinterested in connections to others, with Yoite to the point they’re willing to forgo life completely. Miharu only complies because Yoite threatens to kill his allies, but as time goes on the more he has Yoite in mind as they work together. As Raikou coyly puts it, “rather than friends, you two seem a little more like… Hmm, well… Let’s just say it’s pretty obvious that your concern for Yoite has trumped all else.” They begin with a deadly pragmatic deal, but come to genuinely care for each other as they learn more about the other and sympathize with their hardships.

Miharu grants Yoite’s wish to be erased from existence after they succumb to their withering body, but feels something missing from his life afterword. Eventually Miharu and Yoite’s other loved ones regain their memories. Yoite may not come back to life, but Nabari no Ou says it’s better to be remembered than forgotten because the time they spent together was life-changing. With Yoite dead, it’s not like Miharu and Yoite’s relationship can be “confirmed” with a wedding or epilogue of their future together.

Romance can be read into caring for and accept each other, Raikou distinguishing them from friends, Yoite kissing Miharu on the forehead, and amnesiac Miharu feeling a string connecting his finger to someone else’s. They display physical intimacy, as Miharu cradles Yoite’s decomposing hands and Yoite kisses Miharu’s forehead before they die, but nothing sexual. Other couples–including Kouichi and Raimei, Tobari and Hana, Raikou and Gau, and Miharu’s parents–are equally chaste on the page. Miharu and Yoite have distinct displays of affection, such as Miharu repeatedly tying a scarf around Yoite’s neck. Miharu even fondly looks at a scar left by Yoite from when they were enemies. While violence causes scars and most people consider them unsightly, to Miharu it represents his loved one and their connection. Their relationship leans toward romantic, but can be interpreted as queerplatonic as well. Ultimately Yoite experiences love and acceptance for the first time from Miharu (as well as Yukimi and Hanabusa), and Miharu opens his heart to the world through Yoite. Bonds are important, and sexual or romantic ones are not the be-all-end-all.

Asexuality By Name

Recently, asexuality has been referred to by name in a number of manga. Some of them are even available in English! This number of confirmed characters to justify an article about asexuality in Japanese media would not have been possible even two years ago.

For information on asexual and aromantic characters in English language works, see here:

- The Aromantic and Asexual Characters in Fiction Database

- Ace Character List by Asexuality in Fiction

- Aro & Ace Books

- Ace Reads

Our Dreams at Dusk: Shimanami Tasogare

Shimanami Tasogare is another manga by Yuhki Kamatani, serialized from 2015 to 2018. It follows a year in the life of a young Japanese boy named Tasuku as he comes to terms with being gay. In the middle of a suicide attempt, a mysterious person known only as “Someone-san” invites Tasuku to visit their local LGBTQ-friendly drop-in center.

For most of the manga, neither Tasuku or the audience knows Someone-san’s “deal.” She runs an LGBTQ space, but any LGBTQ identity she has remains unknown. (In Japanese and English, acquaintances refer to Someone-san with feminine third person pronouns. She later describes her gender as whatever other people think, ostensibly making her nonbinary. She’s often at the receiving end of microaggressions against transgender and nonbinary people as well.) She’s willing to listen to any problems the guests of the drop-in center have, but offers no words of advice and keeps to herself. On top of that, Someone-san’s apparent ability to bend the rules of reality (by levitating her body and distorting surroundings) may make the audience unsure if she’s even human or exists outside Tasuku’s mind. By the end, Tasuku learns from another guest of the drop-in center that Someone-san is asexual (aromantic asexual).

At first, Tasuku sees Someone-san’s orientation as an explanation of her eccentricity in his attempt to nail her down as a person. He understands their asexuality as the reason she doesn’t care to be around other people or make deep connections, just as a real person may assume of an asexual acquaintance. However, Someone-san shoots him down by clarifying that being asexual is just one part of herself that can’t define the rest. She just happens to be both asexual and aloof. Someone-san leaves the rest of her identity–gender, disposition, etc.–to Tasuku’s imagination, including how she may or may not be interested in sex. Our Dreams at Dusk implores for everyone to be accepted for who they are, even if not completely understood.

A manga with a major asexual character is already a big deal, but one with an openly asexual creator is monumental. Kamatani provides authenticity to the representation, especially one as tricky as a character who fulfills stereotypes but speaks against them. Please read it if you have the chance.

For more in-depth on asexuality in Our Dreams at Dusk, see here:

- Indispensable Asexuality in Our Dreams at Dusk: Shimanami Tasogare (by yours truly)

- Shimanami Tasogare: the Construction of Identity, the Architecture of Community (by yours truly)

- Shimanami Tasogare: Queer Trauma and Media

Tokyo Ghoul

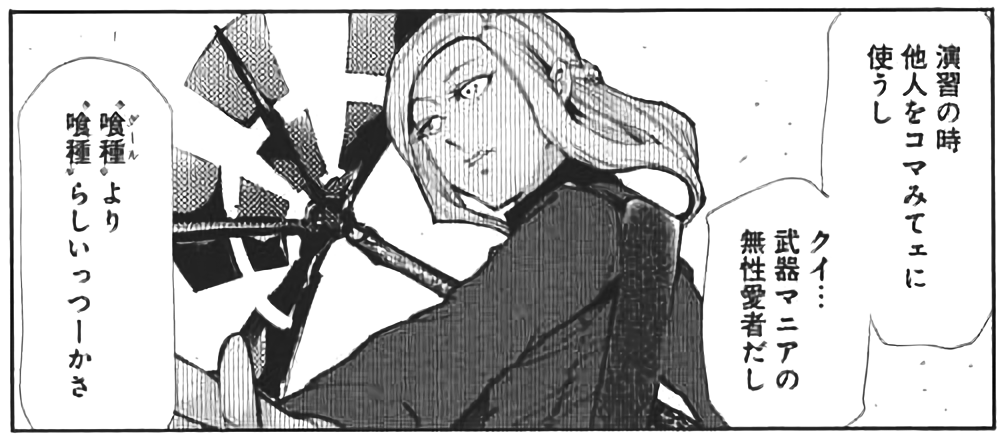

Asexuality coming up in a manga doesn’t always mean a character is asexual, however. Take Tokyo Ghoul, an urban fantasy manga by Sui Ishida where man-eating “ghouls” live among humans serialized between 2011 and 2014, for example. In the ninth volume of the manga introduces a new character named Akira Madou. Her coworkers Hide and Takizawa discuss her over lunch, including Hide commenting on her good looks. In Japanese, Takizawa warns him not to pursue her since she’s “museiaisha” (aromantic asexual) and compares her to the monstrous ghouls. In this case, Takizawa uses museiaisha as an insult for her “inhuman” withdrawn personality and apparent sexual frigidness. It doesn’t indicate her sexual orientation, as later in the manga she falls in love with a man named Koutarou Amon. For more on this from the perspective of a Tokyo Ghoul fan, see this Tumblr post. The official English translation from Viz Media avoids using an identity as an insult and any confusion over her orientation by omitting the word “asexual” or “aromantic.” Instead, Takizawa says she simply has “no apparent interest in anything else.”

Scum’s Wish decor

Scum’s Wish decor, a single volume epilogue to Scum’s Wish by Mengo Yokoyari published in 2017, brings up asexuality directly. While the original series has been printed in English, decor can only be read digitally on Crunchyroll Manga. Scum’s Wish follows a teenage boy and girl who start dating to satisfy their respective unrequited loves for their teachers. It doesn’t address asexuality directly, but does explore the differences between romantic and sexual desire as the characters try to figure out how they truly feel about each other.

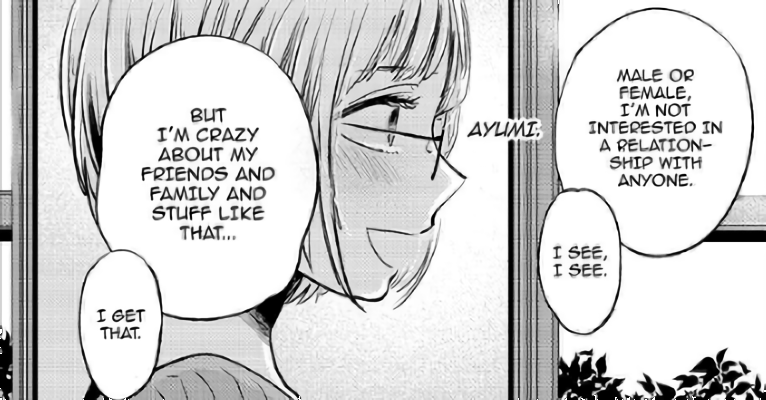

Chapter 4.5 looks at Mito and Ayumi, two minor characters from the original series. In their brief appearance in the original manga, Mito seems to have something to tell Ayumi. In decor, it turns out to be coming out to her friend as asekusharu (asexual). Ayumi always comes to Mito for dating advice, but Mito can’t relate since she’s not interested in romance. Ayumi apologizes for constantly telling her friend to start dating and it makes Mito comfortable enough to come out to her. She accepts her friend, and the chapter ends on a sweet narration for everyone in the world to do the same.

Devils’ Line

Devils’ Line is a manga by Ryo Hanada serialized from 2013 to 2018 about a modern day Japan where “devils,” humans with an inborn addiction to blood and ability to transform into monsters when exposed to it, live among humans. As is often the case with vampires, their bloodlust and sexual lust intermingle. Devils’ Line uses the bloodlust of the devils to explore sexuality, particularly the main romantic relationship between human Tsukasa Taira and half-devil Yuki Anzai. They both have sexual desires for the other, but Anzai’s transformations prevent them from having sex as they make him uncontrollable (as well as extend his teeth into fangs and nails into claws). Like Scum’s Wish, while not about asexuality per se, their relationship examines the role of sex in a romantic relationship. Eventually Taira and Anzai find ways to have sex with harnesses and other devices, with an emphasis Taira’s safety and agency to stop at any time.

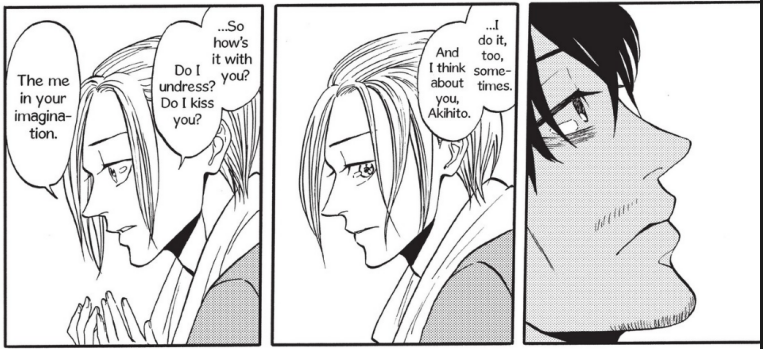

Another couple, human Akihito Kanzaki and devil Eka, have a different sexual barrier in their relationship. Eka may be devil like Anzai, but one closer to human on the spectrum of humans and devils (the titular “devils’ line”) thus not addicted to blood and incapable of transforming. When they meet ten years prior to the main story line, Kanzaki instantly falls in love in with Eka but keeps his feelings secret out of fear. Kanzaki describes two “walls” that keep him from connecting to other people: first that he only likes men, and second that he’s hiseiaisha (nonsexual, alloromantic asexual). The Vertical edition from Kodansha Comics appropriately translates this as “asexual,” as it fits the English meaning of asexual. Devils’ Line shows the complexity of overlapping identities: being gay is hard enough, but even then he worries no man would want to date him if they won’t have sex. A bonus chapter also confirms that Kanzaki identies as x-gender, neither man nor woman in gender. To have individual gay, nonsexual, and x-gender characters would be one thing, but a single character with all three identities is extremely rare and worth celebrating.

Eka confesses being in love with Kanzaki, which brings down the latter’s first emotional “wall” and allows him to admit he’s also in love as well as hiseiaisha. Eka accepts Kanzaki completely even though he’s allosexual, because he wants to make it work even if that means not having sex. They’ve been together for a decade, but have their issues. Early in their relationship, Kanzaki feels guilt over their lack of sex life and wishes his body wouldn’t reject sexual contact. Specifically, he explains to Eka he has a libido that isn’t directed at anyone and he can only handle hugging and kissing.

Devils’ Line makes a point of how Kanzaki’s experiences don’t reflect all nonsexual people, as he states his is only one type of nonsexuality. With that said, on a personal note, Kanzaki’s feelings in his relationship with Eka hit close to home for me. I’ve seen asexual characters before, but not someone gay with an allosexual partner. It’s rather surreal to see something so similar to my life in fiction for the first time, even if in a world of vampires. Ryo Hanada put a lot of care into realistic portrayal of the highs and lows of such a relationship.

Another character in Devils’ Line that could be considered asexual, but probably not because he does not use the word “museiaisha” or “asexual” specifically as Kanzaki does. Kirio Kikuhara, a sadistic and manipulative man, simply says he “cannot love” (including sexual desire). If he were asexual, this could come across as explaining he’s cruelly unfeeling because he’s asexual. More likely, his inability to love could be attributed to his traumatic backstory (another issue to unpack entirely). As it stands, I’m willing to give benefit of the doubt Hanada didn’t intend for him to represent asexuality.

Chii’s Webcomics

Chii is a Japanese trans woman artist best known for The Bride was a Boy, an autobiographical manga about her transition and marriage. The book collected from strips posted to her blog and Twitter account. She has even more strips on the site and uploads new ones weekly about her life, LGBTQ issues, and more. Of course, they’re only available in Japanese.

Some of her comics guest star her husband and friends, including her friend since 2013 known as Aseku-kun. He often gives an asexual perspective on the matter at hand, or Chii illustrates his life to bring attention to asexual issues. She also has a series of strips defining LGBTs identities, including asexuality and nonsexuality and aromantic asexual. Some strips cover cultural exchange, in which Aseku-kun teaches her about concepts from English-speaking communities like romantic orientation or shorting asexual to “ace.” These webcomics strips haven’t been collected into a printed volume in Japan like The Bride was a Boy, which means there isn’t a book to license for English publication. Hopefully more of Chii’s works will be collected in Japanese first. In the meantime, learn Japanese to read them or buy The Bride was a Boy to support an ally to asexual folks!

Aromantic (Love) Story

Kiryuu-sensei wa Renai ga Wakaranai (literally Kiryuu-sensei Doesn’t Understand Love) by Ono Haruka is a 2016 josei manga about the eponymous Futaba Kiryuu and her two unwanted suitors. 32 year old mangaka Futaba has been tasked with creating a trashy harem manga, but her feminist ideals as well as lack of romantic experience give her pause. Her male editor assumes all women enjoy and can write romance, when Futaba has never been in love nor cares for the genre. She’s currently questioning her sexuality, considering she may be asexual or nonsexual because she’s never been interested in men or women. Even though she doesn’t have a label for herself, she’s defensive of sexual minority groups and single women in general when others insult them. This manga contains a lot of biting social commentary on misogyny in the manga industry and society at large.

To make matters worse, Futaba’s younger manga assistant Yuu Asakura and older anime adaptation writer Kyousuke Kitamura both confess their love to her and set off a wacky love triangle. She doesn’t know how to deal with their advances–especially coming from coworkers–or figure out different types of love. Without giving too much anyway, this is not a story where the protagonist finally feels complete when they fall in love.

It is not available in English, but has been localized in France as Aromantic (Love) Story. The French editions embrace the asexual and aromantic element with the title and a color scheme from the asexual pride flag. Please consider requesting it for licensing in Seven Seas Entertainment’s monthly reader surveys to have it in English.

Aro/Ace-Applicable Characters

Even with increases in asexual visibility, there would only be so much to discuss if we limited to confirmed characters. This section looks at characters that can be interpreted as asexual. Although not definitive representation, they’re worth examining because characters with qualities shared by asexual people can still inform an audience’s perception of asexuality for better or for worse. Plus, sometimes they’re just fun to think about.

One Piece: Monkey D. Luffy

Monkey D. Luffy, the protagonist of One Piece (1997-) by Eiichiro Oda, is the most common character brought up when it comes to asexuality in anime and manga. In the context of One Piece, he sometimes does not express sexual desire when other characters would. For example, the character Boa Hancock has the superpower to turn anyone to stone if they have sexual desires by directing those desires at herself. Luffy is immune to Hancock’s power, due to a lack of lust that can’t be manipulated toward her. Hancock becomes fascinated by Luffy and falls in love with him, but he would rather be friends than marry her. English-speaking fans often interpret him as asexual and aromantic because of his disinterest in sex and romance. For more on Luffy from the perspective of a One Piece fan, see this particular post and the rest of the luffy-is-aroace Tumblr blog.

When asked if any of Luffy’s crew would fall in love, Oda responded that “they’re all in love (with adventure).” This brings us to the issue of romance, or lack thereof, in shounen manga like One Piece. Shounen manga often lack romance, or at least lack romantic arcs. Side female characters may have crushes on a male protagonist, established married couples may exist, and main characters may get together in the end; but romance is not focal. Luffy is only one of many male protagonists in shounen manga oblivious to feelings of love and/or sex. There are rarely central romantic relationships as there in shoujo manga, because editors believe their coveted boy readers don’t care for romance. In a heteronormative society that defines romance as a man and a woman, it would also require female characters having more presence in a story (which supposedly boy readers would dislike). Instead magazines like Shounen Jump place importance on themes of “friendship, effort, and victory.” As a result, it can be hard to gauge whether a shounen manga upholds friendship and camaraderie out of reverence for platonic love, or because of the stereotype that boys enjoy action and adventure more than romance as genres. Lack of different-gender romance also doesn’t guarantee sexual minority acceptance, as shounen manga frequently stereotype and caricature gay men and transgender women. Use your best judgement. Nonetheless, fans can find comfort and meaning in manga such as One Piece and its portrayal of friendship and openness to asexual and aromantic interpretation.

Sailor Moon: Rei Hino

Rei Hino, also known as Sailor Mars, has quite different characterization depending on which version of Sailor Moon we’re talking about. In the classic anime, she’s a temperamental and comedic character. Her fiery personality comes out often in her pursuit of boys, even competing with Usagi for Mamoru’s affection. In the manga by Naoko Takeuchi the show was based on, she’s a stoic girl who takes her duty as a shrine maiden seriously. This also goes for Sailor Moon Crystal, a more direct adaptation of the manga.

Rei’s disinterest in dating also defines her character in the manga. She differs from her fellow inner senshi interested in boys, which doesn’t imply an attraction to girls as with lesbian couple Haruka and Michiru. Shrine maidens like Rei aren’t necessarily celibate in real life, but she aspires to care for the shine without having to marry to financially support it. In the Dream arc, the Dead Moon Circus lures Rei into a house of mirrors to force her to give up being a senshi. A fake mirror version of herself tells her can’t stay a shrine maiden devoted to her friends forever and encourages her to fall in love with a man instead, but she breaks through with the help of her pet crows in human form.

Rei isn’t “officially” asexual, but her experiences may resonate with asexual readers who feel expected to fall in love or have sex. Sailor Moon says not every person is fulfilled by falling in love or getting married, which is a good message regardless of orientation. In a series about the power of love, that doesn’t only mean romantic love. Rei’s power and passion comes from love for her friends, family, and pets.

Bloom Into You: Seiji Maki

Bloom Into You, a yuri manga serialized since 2015 by Nio Nakatani with a 2018 anime adaptation, has been much discussed with regards to asexuality and aromanticism in English-speaking spheres. From the premise, you can see why: the protagonist named Yuu Koito thinks she’s incapable of falling in love. When a male schoolmate confesses his love to her, she doesn’t experience the overwhelming joy she expects based on romance fiction and ghosts him. Things get more complicated when Yuu meets Touko Nanami, a year above her at her new school. Yuu overhears Touko turn down a love confession because she won’t ever fall in love, and she thinks she’s found a kindred spirit. They get to know each other, but Touko soon admits falling for Yuu. They begin a physically intimate relationship on the understanding Yuu won’t return her feelings. In fact, Touko prefers it be unrequited for personal reasons. There is truly a lot to unpack here, in terms of sexuality and relationship-building.

First is the fact this is a yuri manga, and thus a romance. Yuu gradually develops feelings for Touko. However, that doesn’t entirely rule out asexual and aromantic readings because those identities exist on spectrums. As I explained in another post, Yuu loving Touko isn’t inherently contradictory to asexuality because a-spec lesbians exist. Ultimately, all interpretations speak to shared experiences in a heteronormative society. Even in terms of Yuu or Touko eventually falling love after declaring they won’t, the manga does so with care. It’s not a matter of inevitability that all people “settle down” or a storytelling cliche, but one of Yuu and Touko’s psychology and character development.

More importantly, Bloom Into You makes it clear through another character that Yuu’s situation is unique to her. When fellow student council member Seiji Maki learns of Yuu and Touko’s arrangement, he relates because he’s also never been in love. In another instance, he says he “doesn’t have a type” when asked to choose between two types of girls. He explains himself to Yuu as enjoying other people’s relationships like one would a stage play, but not wishing to perform in it. ADR director David Wald has referred to Maki as an asexual character the same way he describes the main couple as lesbians, despite neither word being used in the script. Although not explicitly stated, it makes the most sense for Maki’s character. While Yuu is up for debate, Maki provides aromantic and asexual representation as well as another perspective on love. It shows being aromantic asexual does not mean being uncaring or disinterested in romantic love, but that they can appreciate it in their own way.

For more in-depth looks at Yuu and Bloom Into You, see here:

- Bloom Into You and Exploring Asexuality

- Bloom Into You (and Me), a Story About How Representation is Important

- TomoChoco Episode 22: Growing and Becoming

My Love Story: Makoto Sunakawa

My Love Story is a shoujo manga by Kazune Kawahara and Aruko that ran from 2011 to 2016, with an anime adaptation from 2015. The “love story” in the title refers to one between protagonist Takeo and his girlfriend Rinko, but Takeo’s best friend Makoto Sunakawa is of interest here. Ever since they were kids, girls have ignored Takeo romantically and sought out the more conventionally attractive Suna. However, Suna turned down every one of them and would go as far as to say he hated them. Early on in the series, Takeo discovers Suna rejects those girls because they would insult his best friend and he wanted nothing to do with them.

Potential girlfriends disliking Takeo isn’t the only reason Suna doesn’t date, as he says he finds dating boring. In general, he is reserved and introverted. When a longtime admirer named Yukika Amami finally confesses to Suna, Takeo and Rinko encourage him to give her a chance because they can tell she genuinely cares for him. They get to know each other on a double date at the zoo, but Suna still doesn’t feel the same way. The manga focuses on how Yukika’s feelings were worthwhile even if unrequited, but on Suna’s side it seems even an “ideal” girlfriend isn’t necessary. When Takeo says he hopes Suna will find someone he likes one day, Suna replies he’s “having a great enough time as is.” He’s fulfilled by his friendship with Takeo, not a romantic relationship.

Suna has also been interpreted by readers as gay, specifically in love with Takeo. Instead of arguing over whether him being gay or aroace is “correct,” since neither is official, it’s better to consider what those experiences have in common. My Love Story says that no one is obligated to date, which is comforting to people of either identity. With that said, Suna may more likely an intended “herbivore” character. He is one of many male characters (including Yusuke below) that may tap into the sensationalism around herbivore men.

Persona 5: Yusuke Kitagawa (by Modulus)

Persona 5, created by Atlus and released in English in early 2017, tells the story of a group of teenagers taking on larger and larger faces of institutional corruption within current era Tokyo. Similar to the previous games in the Shin Megami Tensei: Persona series, the protagonists face themselves in order to grow and summon Personas, or physical incarnations of the faces they show the world. Yusuke Kitagawa, one of the members of this team, is a vital member of the group and adds a certain charm; from his first introduction and onward he is described as incredibly unusual and eccentric, disregarding “normal” ways of regarding the world in his passion for depicting all things artistically. This is generally highlighted by his disregard for the connection between sexuality and nudity as he regards the human body as aesthetically beautiful.

Throughout the over 100-hour game, I recall sensing multiple times that Yusuke could easily be interpreted as an asexual character. Multiple scenes, such as during his introduction of demanding one of the other protagonists be a nude model for his next painting, and another scene where he describes the power of the composition of a famous nude masterpiece, show Yusuke having no awareness of the potential sexual nature of the unclothed human form. This disregard is seemingly equal with both AFAB and AMAB bodies, as at least one scene for each is shown in game and displays his disinterest equally.

Many of the other protagonists comment on this obliviousness, uncomfortable with what they interpret as licentiousness. His persistently confused responses throughout the game seem to confirm that his lack of awareness is not an act; he is simply disinterested. This was a very relatable experience to me as a fellow asexual person. Unfortunately, his depiction is not textually described as queer in any way, and only ever depicted supposedly humorous insult. Atlus could have explained this character better, with its narrative voice, though this is not an uncommon issue in Atlus publications.

Odin Sphere: Gwendolyn and the Valkyries (by Modulus)

In yet another bad example by Atlus, the 2007 game Odin Sphere and its 2016 remake Odin Sphere Leifthrasir depict an entire species where what could be described as asexual aromanticism is culturally common. Taking the player into a world full of supernatural species at war with one another, Odin Sphere’s story is told through five playable characters living through the same events from different perspectives. The first playable character, Gwendolyn, is from a race of bird-like warriors intending to colonize the known world. In this race, cis-women warriors are considered much stronger than their cis-men counterparts. Unfortunately that’s a lot less subversive than it sounds, as these valkyries are raised within a culture that informs them their only way to earn an ideal afterlife is to die valiantly on the battlefield. Should they survive long enough, they will be captured by their own kind and cursed into a deep sleep with their only chance of awakening occurring via the kiss of an arranged spouse. The coma-inducing spell also includes an effect of forcing the subject to become attracted against their will to their betrothed. At least one scene shows a man from this race coveting the bodies of valkyries returning from war, and another shows a valkyrie weeping and begging to be sent to her death when informed it was her time to be married. It is difficult to put into words how damaging this depiction of forced sexuality can be for an asexual, and especially female ones.

To make matters worse, about halfway through the game it is established that this curse is placed on our main character for the political gain of her father, the king. After waking in the arms of one of her war rivals, she is shown to be horribly repulsed by him and the concept of love itself, and continues to be in several scenes. She is shown, therefore, to be clearly suffering emotionally due to the manipulative nature of the magical love curse. Despite all of this pain Atlus and Vanillaware have depicted, however, they shows no awareness of the plight of real sex repulsed nor aromantic asexual people, giving the player an emotionally conflicting story ending in which Gwendolyn eventually chooses to live with her assigned husband and “fall in love with him,” supposedly due to the fact that he’s the first person in her life that’s ever treated her like an individual worthy of respect. This continues into the entire game’s final ending as Gwendolyn becomes the prophesized “mother of all humanity” after the world’s apocalypse. While I am personally glad that this character could be given an ending in which she appears “happy,” as a sex repulsed aroace person I felt myself feeling ignored and rejected.

Metal Gear Solid: Psycho Mantis (by Modulus)

Psycho Mantis of Metal Gear Solid fame is, perhaps, a better known example of Japanese characters on this list to the gaming community. Originally released in late 1998 in Japan and the US, and early 1999 in Europe, Metal Gear Solid for the PS1 continues the story of Solid Snake from earlier NES games. The series follows the main character, a US soldier with the code name Solid Snake, through his missions to prevent major strikes against the United States. Metal Gear Solid itself follows Snake as he attempts to prevent FOXHOUND, a US black ops team gone rogue, from enacting its plan to launch a nuclear strike within 19 hours of the beginning of the game. As Snake attempts to infiltrate FOXHOUND’s hideout and neutralize the threat, one of the first members of the group he encounters is a character with telepathic and telekinetic powers code named Psycho Mantis.

This particular character stood out to me in early in life, and continues to do so for several reasons. While most people likely remember Psycho Mantis’s encounter for its 4th-wall breaking storytelling in the middle of a somewhat serious game and the gratuitous emphasis upon his murderous intent that is supposedly inspired by past trauma and mental illness, Psycho Mantis was further complicated for me as an asexual child by the fact that Psycho Mantis also expresses distinct sex repulsion. In his defeat speech where he states his rationale for joining FOXHOUND’s plan, Mantis explains that, through his lifetime of examining the minds of other people, he became disgusted with “[humanity’s] selfish and atavistic lust to pass on one’s seed” and that this caused him to follow the plans solely for the sake of “killing as many people as possible.”

On top of all of the other problems this character’s writing has, making a serial killer character experience one of the possible traits of asexuality and using it as a reason for why he murders is incredibly harmful. It was, therefore, difficult for me to parse as teenager attempting to examine why I felt so differently from others about sexuality. Psycho Mantis can easily be read as an asexual, perhaps even aromantic, character, but as far as representation goes for the asexual and nonsexual communities within Japanese media he is yet another poor example.

Aro/Ace-Appealing Relationships

After those negative examples, let’s end on a good note. This section is for relationships that may appeal to asexual and aromantic audiences, whether interpreted as queerplatonic or involving asexual or aromantic characters. Again, while not “confirmed,” we recommend them if you’re looking for fiction with such relationships at the forefront.

Banana Fish: Ash & Eiji

Banana Fish is a classic shoujo manga by Akimi Yoshida serialized from 1985 to 1994, with a much later anime adaptation in 2018. The story follows Eiji Okumura of Japan on a photography assistant job to document youth gangs in New York City. There he meets Ash Lynx, a white American gang leader who immediately takes a shine to him. Meeting Ash pulls Eiji into a turbulent world of mind control drugs, the mob, government conspiracy, child trafficking, and death. Despite the danger, Eiji stays by Ash’s side to love and support him. The more time they spend together, the more Eiji learns about the hardships Ash has been through, including child sexual abuse and child trafficking.

The series touches on sexual assault throughout, making it clear that sex and love are not the same, as Ash decries rape as an action rooted in power rather than attraction. Ash has been treated like an object sexually for most of his life. Even if people don’t sexually abuse him, they rarely treat him like a person and more like a force of nature. Eiji does neither of those things because he has no preconceived notions of Ash as a dangerous gang leader nor rape survivor, just a teenage boy. From there, Ash can let his walls down emotionally to voice his fears and physically to be embraced. Eiji sees him in a loving light and–whether or not he’s sexually attracted to him–would never betray that trust and assault him. Their close relationship is widely interpreted as romantic and queer.

Ash is sometimes interpreted as asexual by fans, and there is a case to be made for Eiji too. Ash’s history of child sexual abuse may complicate any potential orientation identity–gay, bi, asexual, etc.–which is outside the scope of this article. However, it would be simplistic to use his history of abuse to “prove” or “disprove” any identity definitively. It would be dismissive, as real survivors of sexual violence are capable of adopting whatever identity and terminology they choose. For example, in the 2016 Ace Community Survey 12.9% of asexual respondents had experienced non-consensual sex and 37.5% non-consensual sexual contact. Identifying as asexual and having experienced sexual violence are not mutually exclusive.

Ultimately, Ash and Eiji don’t have “official” orientations. Mangaka Akimi Yoshida doesn’t label them or their relationship. Like Miharu and Yoite in Nabari no Ou, Ash dies before their relationship can develop into something more “definitive” and before he could possibly become comfortable having consensual sex. All we’re left with is that they loved each other in the time they had together. In the epilogue chapter “Garden of Light,” a friend of Ash and Eiji’s explains their relationship: “Which doesn’t mean their relationship was sexual, because it wasn’t. But they did love each other… maybe the way lovers do. They were… connected to each other, soul to soul.”

For more in-depth looks at Ash and Eiji’s relationship, see here:

- More than Friends, More than Lovers: Exploring Ash and Eiji’s Love

- Japanese LGBTQ+ fans talk about the legacy of Banana Fish

- 12 Days of Anime: The Power of a Photograph (by yours truly)

Rozen Maiden: Jun & Shinku (by Modulus)

The next set of characters we’ve chosen to display aroace types of relationships is admittedly a bit confusing to announce, though chosen with intent. Rozen Maiden by Peach-Pit, best known for its anime released in 2004, spans eight translated books once published by Tokyopop and an untranslated sequel which received another anime adaptation released in 2013. The story follows a middle school aged boy and local acquaintances brought together by eight magical, sentient, ball-jointed dolls. Said dolls, created with the eternal desire to become a perfect girl to win the love of their creator, fight one another to collect the equivalent of one another’s life force to accomplish this task. Their ability to stay conscious in this fight and use their combat magic, however, rests upon their ability to make an energy-sharing contract with a human medium.

Despite sounding like a traditional shounen series, much of the plot actually hinges on the relationship dynamics of the Rozen Maiden dolls with their mediums, and with their other sisters throughout this war. The main character, Sakurada Jun, is introduced early in the series as the begrudging new medium for a doll named Shinku. Their personalities are immediately at odds as Jun’s immaturity, bitterness and insistence on remaining a shut-in from the world clashes with Shinku’s noble, but stuffy and stubborn nature. They quickly begin to unravel one another’s life struggles, however, as Shinku begins to assist Jun in addressing his public humiliation trauma, and Jun provides enough of a stable home for Shinku to begin addressing the grief of either losing all of her sisters, or the loss of a future with her beloved creator.

Their relationship together was notable to me as a young aromantic asexual person for a number of reasons; this series is notable for how most of its visual art to leans towards metaphors commonly used with romances in spite of the fact that this series contains none of note. This may have been an intentional subversion by Peach-Pit of symbolism used in depictions of romantic relationships. For example, a Rozen Maiden’s contract creation involves the new human medium kissing the ring finger of the doll. A rose-shaped ring is then created upon the medium’s left ring finger which symbolizes their bond. Also, the opening theme song of season one of the original anime uses surprisingly flowery, passionate visuals and lyrics as it describes Shinku’s conflicted feelings as she sets aside her longing for her father for Jun’s sake. This is especially notable in that a common theme of romance stories involves leaving the family of origin for a romantic partner.

Despite all of these symbols, Jun and Shinku are never in my knowledge depicted to be romantically interested in each other despite part of the narrative involving Jun as a college-aged young man. Throughout all of their interactions and joint struggles, they create what I can only describe as a deep platonic bond. This deep platonic bond attracted me the most to this series, as it could be argued as mirroring the deep kinds of platonic bonds that some aromantic people seek out.

Steins;Gate: Hououin Kyouma & Mayuri (by Modulus)

The next example I’d like to talk about is one of the main relationships within the anime version of Steins;Gate. Created originally as a visual novel by 5pb. and Nitroplus and set loosely within the same universe as Chaos;Head and Robotics;Notes, Steins;Gate chronicles the mild misadventures of a group of degenerate young adult friends building strange contraptions in a rented apartment space. The twist of the show occurs when one of their fantastical, somewhat intentional joke inventions actually works at creating a functional time machine. Due to the way they constructed it and how they had hacked the systems of a large science research organization to do so, they discover that the changes they made to their own pasts have created a future in which their time machine is converted into a weapon used to enslave humanity.

The main way this affects the protagonist, Rintaro Okabe, is in how it creates a persistent event across each iteration of similar timelines: his best friend since childhood, Shiina Mayuri, dies somehow at the same date and time in each one of them. Okabe is shown to be devoted to her safety enough to travel across dozens, perhaps hundreds, of timelines in an effort to prevent her death. His grief is realistically depicted throughout the trial, and nearly destroys him.

Throughout his effort, however, the anime makes a point of having him clarify that his love for her is non-romantic and he never intends to make it anything else. He is even shown comfortably having romantic attraction to another character later, which Mayuri is never shown having issues with. Okabe and Mayuri’s relationship could be described as somewhat familial due to events in their childhood together. They could also, however, easily be interpreted as having a queerplatonic relationship. Mayuri herself, never showing interest in anyone romantically or sexually throughout the anime, could also be considered asexual or nonsexual.

That’s All Folks!

Hopefully more anime and manga will include asexual, nonsexual, and aromantic characters in the future. I hope to keep hosting this panel with Modulus at anime conventions. If you enjoyed this article, you can support me with a tip by buying me a coffee. Thank you!

Yay, it’s finally here! Thanks for writing this all up, it was a really interesting read!

LikeLike

Thank you for this exhaustive list! It must have taken you a long time to put together, and it’s a really valuable resource!

LikeLike

This is a great review – I had no idea there was so much new stuff out there now! And you’ve inspired me to finally finish reading Nabari no Ou 🙂

LikeLike